Refusing at Fifty-Two to Write Sonnets

by Thomas Lynch

It came to him that he could nearly count

How many Octobers he had left to him

In increments of ten or, say, eleven

Thus: sixty-three, seventy-four, eighty-five.

He couldn’t see himself at ninety-six—

Humanity’s advances notwithstanding

In health-care, self-help, or new-age regimens—

What with his habits and family history,

The end he thought is nearer than you think.

The future, thus confined to its contingencies,

The present moment opens like a gift:

The balding month, the grey week, the blue morning,

The hour’s routine, the minute’s passing glance—

All seem like godsends now. And what to make of this?

At the end the word that comes to him is Thanks.

![0805 [Doris Day] DANCING_(c)_Leo_Fuchs_Photography_(www.leofuchs.com)(www.theheliosgallery.com) by The Helios Gallery](https://i0.wp.com/farm4.static.flickr.com/3315/3344542668_19121261f6_m.jpg?resize=190%2C240)

This poem has me thinking about Doris Day, and not just because I think poet Thomas Lynch is adorable. (Imagine Jack Black balding, gray and bespectacled.) In so many of her movies, Doris Day begins with a firm resolve–I will not fall for a womanizing phone-hog I despise, I will not fall for a newspaper editor who doesn’t respect education, I will not fall for the pajama factory foreman who won’t give the workers the raise they deserve—and then she’s duped into falling in love with the very men she and her perky principles had refused to consider.

And so with this poem. The poet who refuses to write sonnets has written a sonnet.

Granted, “Refusing at Fifty-Two to Write Sonnets” is not technically a sonnet. From what I gather, a sonnet has four defining characteristics:

- has 14 lines

- has a specific rhyming pattern, depending on whether it’s Petrarchan, Spenserian, or Shakespearian.

- usually written in iambic pentameter

- operates on what is called “the turn.” The first part sets forth a question, emotion or issue, and the second half responds in some way, resolving or contradicting.

Lynch’s poem misses two of the four criteria. “Refusing” has 15 lines and has no rhyme at all, beyond the clever consonant rhyme of “think” and “thanks,” the two words which end each section of the poem.

But Lynch has something up his sleeve here. The poem is written mostly in iambic pentameter, and 15 lines is so close to 14 that methinks he doth protest too much. If a poet were really intent on not writing a sonnet, he would likely come up with something more like Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, pages and pages of long, loose lines.

Besides, it’s “the turn” that’s at the heart of a sonnet, and the turn here is so clear it could be marked with flashing lights and a “Street Closed” sign. The poem physically separates at the tenth line; the verb tense changes from past to present; and most important, the mood changes from resignation and dread to gratitude.

In the first stanza, a man who seems to be a poet wonders how many years, at age 52, he has left to live. He tries to count them but numbers so overwhelm him that he loses count of his sonnet and writes nine lines instead of eight. His overthinking about the future (remember that this stanza ends with “think”) keeps him in the grips of a morbid mood.

The turn in the second stanza moves into the present. He gives a wonderful description of October:

the balding month, the grey week, the blue morning,

lines which describe himself and his mood as well.

From the month, he moves to the week, then the time of day, and finally to the very moment (the minute’s passing glance) within which he exists. Only then is he able to move beyond his fear of death and feel gratitude for living.

If you’ve ever escaped from a health crisis or scare, a sudden brush with death, or as in the case of this poem a self-induced death watch, you understand the gratitude expressed at the end of this poem. All the sudden you realize that right now at this moment you’re alive. You get up from your knees, from your trembling and nauseau, and you can’t believe how wonderful the world is. Life is so great! Wake up, wake up! you want to say to everyone who complains about little things like dreary weather, inconveniences, annoying people. Life’s a marvel, even the falling leaves, the rain clouds, the dark mornings. So great!

But because the poet is not George Bailey pulled back from the bridge all wild-eyed with happiness, but Thomas Lynch, wry and bemused, the turn in this poem is quiet. Thanks. Emotion is contained. The containment is partly because Lynch is Irish, and the Irish are champs at containing emotion, but also because sonnets are champs at containing emotions. Writing a sonnet places limits on the writer—limits of line length, meter and structure—and those limits allow an expression of deep emotion that is very civilized. Would that all problems could be so contained.

“Scorn not the sonnet,” Wordsworth wrote. I’m sure Lynch would agree, so what to make of his refusal to write one? For one, he seems impish and doesn’t like to do what’s expected. He counts by elevens rather than the standard ten. He writes 15 lines instead of 14, perhaps because he wants more. The first stanza is about the limits of the years he has left on earth. He wants to go over the limit. Life is too big, even at 52, to follow prescriptions.

(Interesting that another meditation on the same themes of autumn and death, Hopkins’ “Spring and Fall to a Young Child,” is also, at 15 lines, an almost-sonnet.)

Anyone writing about Lynch has to figure out how to put a fresh spin on the fact that he’s an undertaker and a poet. There, I said it. Lynch himself draws the best parallels between his two professions. In an interview he once said, “It is the same enterprise: to organize some response to what is unspeakable. We need a way to say unspeakable things, and funerals do. So do poems.”

I have a special feeling towards Thomas Lynch. I’m inclined to like anyone who shares my background, that is, Irish and Catholic, but he’s also a funny and wise writer, and a native of Detroit. He went to the same high school my son just graduated from, and his book of essays, The Undertaking, is a favorite of mine.

Born in 1948, Lynch splits his time between his hometown of Milford, where the funeral home Lynch and Sons still operates, and County Clare, Ireland. He’s won a number of awards for his poetry and his essays. If you ever get a chance to hear him read, go. He’s entertaining as only the Irish can be.

Okay, enough with the Irish.

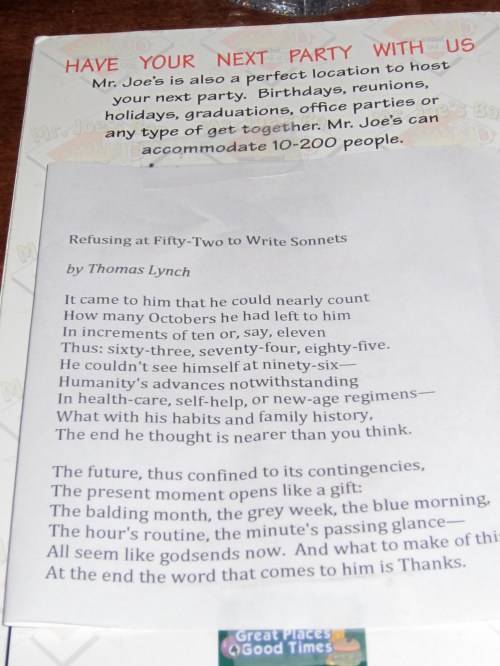

I left the poem in a local watering hole. It was a dark place, with all the trappings of a man’s gathering space, big screen televisions, wood paneling and brass rails. At the bar three or four men slumped in front of their beers. It all felt sad to me, and I found only irony in the lines which appear under the poem in my photograph: “Great places, good times.” But then again I’m Irish and inclined to darkness.

Now that I can count my decades on one hand, I find sonnets gush forth, a mighty slush gravure like a snowplow sculpts a degree or two below freezing, mighty banks that break like waves in a Japanese print, each finger marking where a lighter area resisted the sun and a dirtier area gave in and melted back. I might bother to rhyme, but enough if the consonants are constant or at least consistent. Or at least continent. No problem rhyming kotex or stolichnaya when my sonnet is moving boxes, packed with tons of books and picobytes of DVDs, a little hungover and unshaven. Probably a day laborer picked up from the lumberyard parking lot. The sonnet smells bad, too, the greasy hair, the dickies work pants laundered a few weeks ago. My wife nudges me and urges with her eyes to watch this guy, but to be sure to feed him and give him a change of clothes and offer him a shower before he leaves. If there were a commandment from Sinai, reconstructed from a shattered tablet inscribed with lightning by the arc light from Jehovah’s finger, it might be You can be smart and be a good person too. Thou shalt not be an asshole.